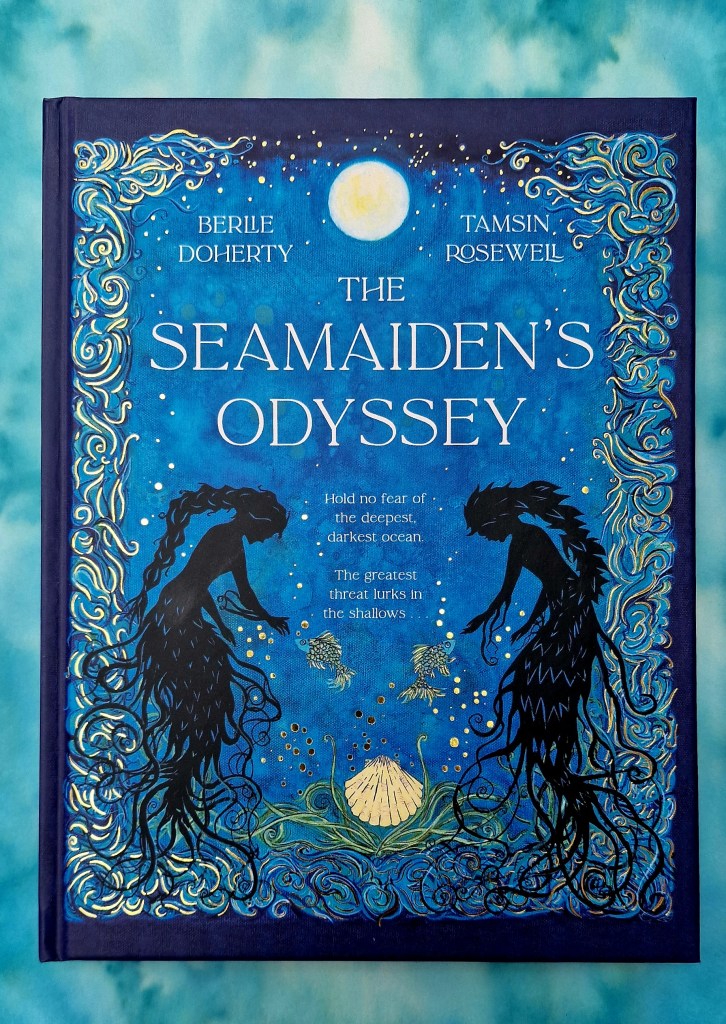

To celebrate the publication of The Seamaiden’s Odyssey, we let both author and illustrator take over our blog as they ask each other questions on their writing and illustration process, and how they create the magic inside its pages.

Berlie: I’m really interested in how an illustrator adapts to the challenges of creating underwater scenes.

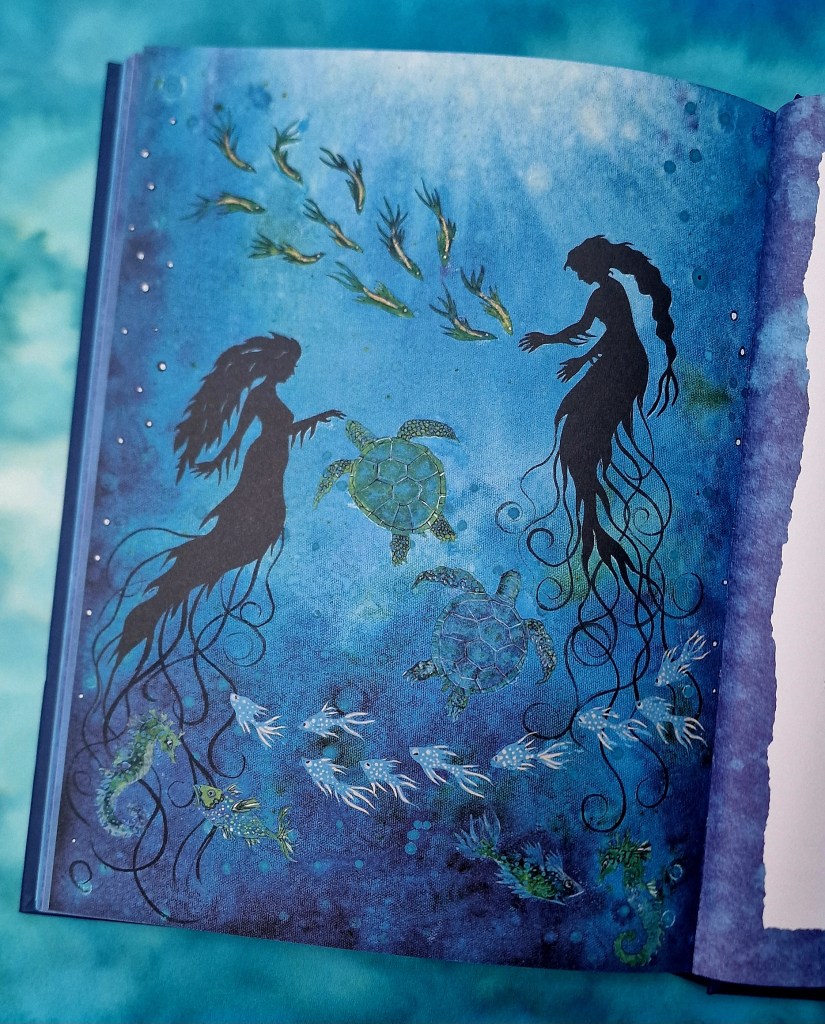

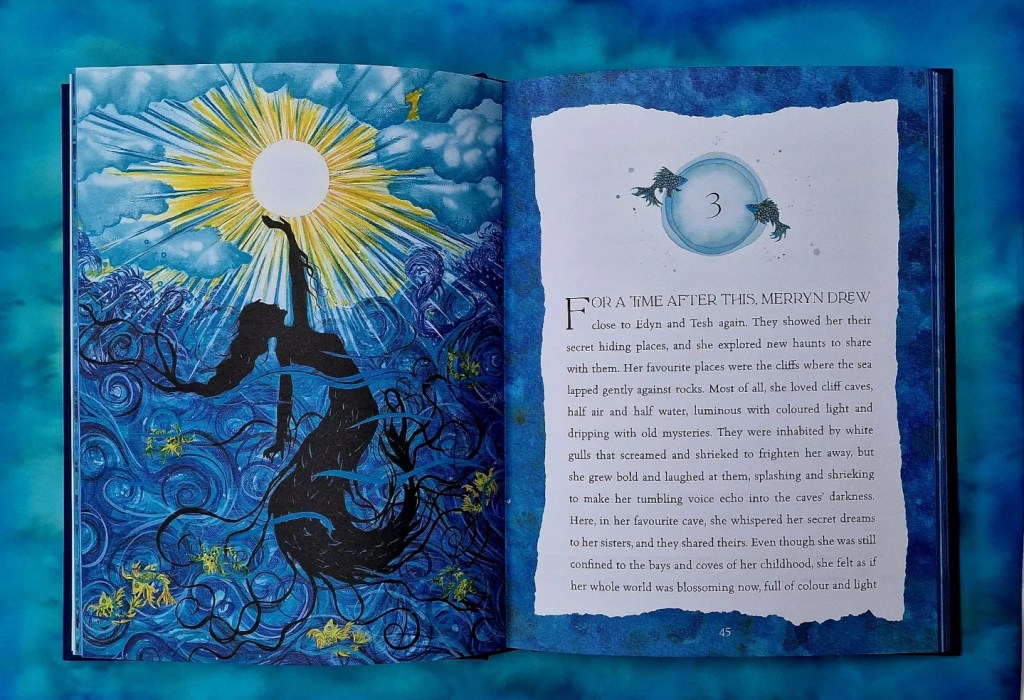

Tamsin: I loved finding ways to create that wateriness. I work in ink, which lends itself very well to the movement of water, and the way light plays in it. Water has different moods, it isn’t one landscape. I used everything from undulating, marble-like colour for calm ocean, to lots of tiny, quick brush strokes, combined with grand structural movement of waves, to create dramatic, stormy landscapes. Both those ways of painting water could then be a real contrast to the dark, stagnant water in deep caves or pools – a very different environment again.

How do you write characters underwater? Everything is different for them, from the sense of space, to the way they move.

Berlie: Yes, it did have its challenges! I had to remember not to make my characters walk, run or stand! The characters in this story are at home in the sea, just as we are on land. I created my sea creatures to think, react, feel emotionally, solve problems, long for, feel love, despair, grief, anger and pain in ways that we can identify with, yet whose reactions to water and all its moods, currents and power are those of creatures living in their true element. The oceans are vast, and I wanted to give a sense of that vastness as a contrast to the confinement of the inland pool.

Working in silhouette is a very classical language of illustration but how do you adapt your style to painting character as silhouette?

Tamsin: Silhouette has a really long history in storytelling – in fact we can trace it back to neolithic art, and the figures on Ancient Greek vases! It is part of human social history. To use it well, you need to do two things; firstly be very precise on profile facial expression and gesture – hands are vital! Secondly you need to make sure that your background colour, texture, structure and landscape is also telling the story. You need to use the whole image.

So many of your stories have their origins in folklore, which is also part of social history – why do you think folklore is important for today’s young readers?

Berlie: Folkloric stories have explained the inexplicable throughout time, long before any were written down. They warn against danger (don’t go into the woods because dangerous animals lurk there, don’t go near water or an evil spirit will pull you in). They open up our imagination to mystery, wonder, humour. They make sense of our world and our imaginings, and they reach far, far back through generations and ages and keep us in touch with the beginnings of society and the spoken word. We don’t let go of them because we can’t; they’re part of us, and no child’s life should be without them.

I have always thought of the relationship between the story text and the artwork in musical terms – the author is the composer and the artist is the instrumental interpreter. But you were in at the very beginning of this book. How would you describe the relationship?

Tamsin: I think music is a really good way of thinking about this! In my mind colour is very closely connected to music, with it you can create atmosphere and drama, and really add to a story. And in this book of course, I also had the chance to paint music; the song of the seamaiden, that was a wonderful challenge! I think maths is really important too – it is the structure of an image that guides someone’s eye around it. I often spend ages measuring and marking up a canvas before I put any ink on!

You’ve got a strong music background too, is music something you associate with written storytelling?

Berlie: Absolutely. One of the mantras I pass on to young writers is to always read their story out loud, so they can listen to the music of the line. There’s a place for the staccato, there’s a place for the lyrical, there’s a place for the easy flow of crescendo and diminuendo. Some people love to write with music playing in the background. I can’t, because it distracts me. But sometimes I deliberately listen to music in the foreground, shaping my story to it, as in Blue John and Daughter of the Sea. Or sometimes I listen to a particular piece of music before I start, and this helps me to find the right mood and tone for the piece I want to write.

The Seamaiden’s Odyssey is out now and published by UCLan.

Berlie Doherty

Berlie Doherty is the author of the best-selling novel, Street Child, and over 60 more books for children, teenagers and adults, and has written many plays for radio, theatre and television. She has been translated into over twenty languages and has won many awards, including the Carnegie medal for both Granny Was a Buffer Girl and Dear Nobody, and the Writers’ Guild Award for both Daughter of the Sea and the theatre version of Dear Nobody. She has three children and seven grandchildren, and lives in the Derbyshire Peak District.

Tamsin Rosewell

Tamsin Rosewell is an artist, historian and broadcaster with a background in politics. She was a bookseller for 15 years, with a specialist knowledge in children’s and picture books before moving to illustration. She is also known for her painted window displays. Tamsin is a regular panel speaker and Festival event chair, as well as being a judge of the Stratford Salariya Picture Book Prize. She is based at 55-year-old independent bookshop, Kenilworth Books, but divides her time between London, Oxford and Warwickshire.