Interview by Jayne Leadbetter

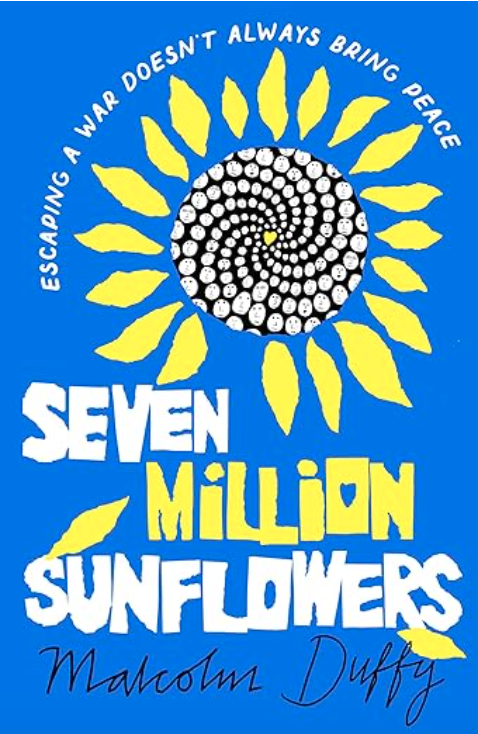

Sofiia Marchenko was 18 years old when she arrived from Ukraine to stay with Malcolm Duffy and his family. Over the year that Sofiia and her mother and grandmother lived there, Sofiia became the inspiration for Malcolm’s story, Seven Million Sunflowers, providing insight into the experiences of a teenage refugee. We were lucky enough to chat to both Malcolm and Sofiia.

Interview with Malcolm Duffy

Could you tell us a little about your book, Seven Million Sunflowers?

This is a book I wish I didn’t have to write.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, 2022, it affected so many lives across the world. Including our own. Having joined the Homes for Ukraine scheme, and inviting the Marchenko family into our home, I discovered the strength, resilience and humility of the Ukrainian people. I learnt what it was like to have to flee a conflict, and adapt to a new country, new language, new culture.

This was the inspiration for my story, Seven Million Sunflowers.

Writing is like making a meal – all the ingredients are important. But I think there was one key ingredient – acceptance.

This novel has many themes, from resilience and acceptance of different cultures to coping with post-traumatic stress disorder and the changing dynamics of a family, to name a few. Were any themes most important for you to include as the writer?

Writing is like making a meal – all the ingredients are important. But I think there was one key ingredient – acceptance. To what extent can you accept strangers in your home, accept the views of others, accept different cultures? This applies to both the hosts and the guests.

The opening paragraph and description of the attack on Kateryno’s building is so vivid – the burst pipes, flames and fire grounds you in the present. What kind of research did you do to help write the book?

I wanted to start the book in as dramatic a way as possible. The story doesn’t reflect Sofiia’s escape from Ukraine, but it does reflect the experience of many Ukrainians, especially those living near the front line, like those in Kharkiv.

The idea for the chapter came from a real event where a Russian missile struck an apartment block in Dnipro, Ukraine. A young woman, Anastasia Shvets, was on the 5th floor of the building. 236 apartments were destroyed and many people were killed, including her parents, but she somehow survived. A photographer captured her, clinging to a small green teddy, as she sat in the rubble far above the city.

The topics you’ve written about must have been very sensitive to discuss with Sofiia. How did you both feel talking about what happened?

For me it’s important to remember that this is fiction, based on fact. It’s not Sofiia’s story or that of her family. I spoke to many Ukrainians when writing the story, as well as reading books and articles on the conflict. The characters are an amalgam of different people I’ve met, and stories I’ve heard.

Sofiia helped me understand the feelings of Ukrainians, the anger and sadness at having been forced from their homeland.

It’s interesting how you describe both external and internal conflicts: the war in Ukraine and Georgia and Marko’s relationship under the same roof. What were some of the challenges you faced as a father inviting a family into your home?

The Marchenkos were a delightful family to have in our home. They kept themselves to themselves, were respectful of us and our home, and helped us when they could. The drama in the book came from stories I’d heard from various sources about problems between host families and their Ukrainian guests. Sometimes the host family were at fault, sometimes the Ukrainians. I wanted to reflect this in Seven Million Sunflowers.

Although this is a work of fiction, you’ve based the book on your personal experience. Do any of the characters in the book resemble you in any way?

I don’t think any of the characters in the book resemble me. Having said that I like to include elements of human nature that mean a lot to me – humour, empathy, kindness, understanding.

Are you working on anything new at the moment?

Yes, I’m working on a new YA book at the moment, but I don’t want to jinx it by talking about it!

Interview with Sofiia Marchenko

The opening to this novel is very powerful. The description of everyday things such as the guitar, desk etc. all upside down amid the fear and the deafness is so vivid. I was almost choking from the smoke. How much of this was true to your story?

I was fortunate enough not to live too close to Russia unlike the heroine of Malcolm’s story. I am fortunate enough that my flat is still not damaged. But I think the early morning of 24th February was frightening for everyone. I woke up from the explosions. Although we all knew war was coming – I didn’t expect to feel it myself in central Ukraine so soon. My town is of an average size – it has 250,000 people. But even this small town experienced some damage during the ongoing Russian invasion. First missiles, then a few months later drones etc.

I was very frightened although I tried not to show it to my friends and family. On the day of the 24th, the first thing I did was go to the local corner shop and buy champagne and my favourite chocolate. This has always amused me but now I understand I probably was thinking they might be my last days on this earth so I’m gonna celebrate my life. After having those for breakfast I didn’t eat anything at all for the next 3-4 days.

On the day of the 24th, the first thing I did was go to the local corner shop and buy champagne and my favourite chocolate.

Kat defends and protects her mother by not translating certain negative conversations. Did you ever have this experience?

We definitely didn’t have a negative experience with our host family. Malcolm and his wife and children are super sweet and supportive. But there definitely were some moments outside of our host family’s house (like dealing with the search for work and accommodation) that were stressful and I didn’t always translate everything to my mum for the sake of her wellbeing. I know she likes to solve problems and support me but with her not being able to speak English, it really left her feeling helpless and I didn’t want to add to that.

Was it difficult adapting to rules in someone else’s home?

As I mentioned earlier – our host family were super sweet and understanding. It wasn’t difficult to adapt to their rules, we are really lucky we met them. We are still friends and love babysitting for their lovely dog Layla sometimes.

What was hard for me was the lack of personal space which I always had growing up. I am an only child and my parents were working a lot, so I had a lot of moments being alone in the house. I am not used to having many people around, so this was hard. I always had some anxiety, even back in Ukraine when we had some guests visiting, so even though our host family were the loveliest and the most understanding people ever, I did miss being alone sometimes – this is an environment where I regain my strength and resources to carry on in difficult times.

How did it feel being in the UK, while people you knew and cared about were still in your homeland?

Definitely a lot of guilt. Feeling you are the lucky one who got away and survived and can carry on having a normal life.

The book is excellent at describing the emotions of a person having to deal with all the mixed feelings of living in two different worlds…

What do you think of the final book, Seven Million Sunflowers?

I have read it and I do love it! I think it is amazing of Malcolm to address this issue through a powerful story like this, and it’s definitely a compelling and moving story. It describes all the difficulties a young Ukrainian teenager faces when escaping the war and having to live a ‘normal’ life while having loved ones in danger every day.

The book is excellent at describing the emotions of a person having to deal with all the mixed feelings of living in two different worlds on the same continent where one is full of chaos and death and other one is peaceful and carefree.

Do you still live in the UK? If so, what are you doing? What plans have you got for the future?

I still live in the UK. We are renting a flat with my mum in a nice area. Currently I am teaching piano classes, mostly to kids, and finishing my Communications degree online. For now, I just want to take time to think about what I actually want and what I am going to do next. To be honest, I didn’t have much time to think about that before.

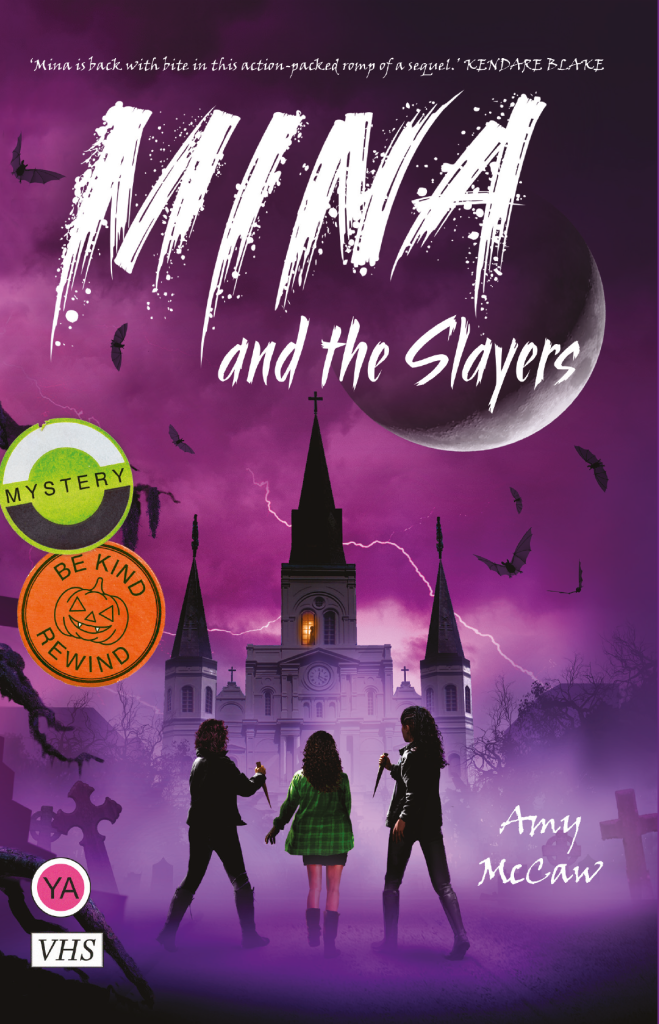

Seven Million Sunflowers is OUT NOW and published by Zephyr

Refugee Week runs from June 17th to 23rd 2024. Read more about it here.

Malcolm Duffy

Malcolm was born and bred in Newcastle upon Tyne and now lives in Surrey. After a typical Geordie childhood, his parents moved south and deposited him in South East England. Having acquired a Law degree at Warwick University he worked his way through a host of London advertising agencies, picking up numerous awards for copy, press, TV and radio.

Having left ad-land he worked as Creative Director of Comic Relief, creating campaigns for Red Nose Day and Sport Relief. It was at Comic Relief that he was inspired to swap copywriting for writing and wrote his first novel, Me Mam. Me Dad. Me. His books have all been issue based, with much of the information gleaned from his work for different charities – Comic Relief (domestic violence), Shelter (homelessness), Nessy (dyslexia) and Combat Stress (PTSD).

He’s supported in his efforts by his New Zealand wife Jann, and daughters Tallulah and Tabitha, who, under the threat of withholding pocket money, seem to like what he writes.

Find out more at malcolmduffy.com and follow him @malcolmduffyUK

Huge thanks to Jayne Leadbetter for preparing the interview questions. Jayne has also reviewed Seven Million Sunflowers in our Spring/Summer 2024 issue, which you can download for FREE here.

Jayne Leadbetter

Jayne Leadbetter emigrated to Australia from the UK and is a high school teacher at a multicultural high school in Sydney, where she lives on the land of the Gadigal and Bidjigal people. She’s currently studying for a master’s degree in creative writing at university and is in the process of writing two novels, while enjoying the nature and the beaches of Australia with her huge dog Clifford.