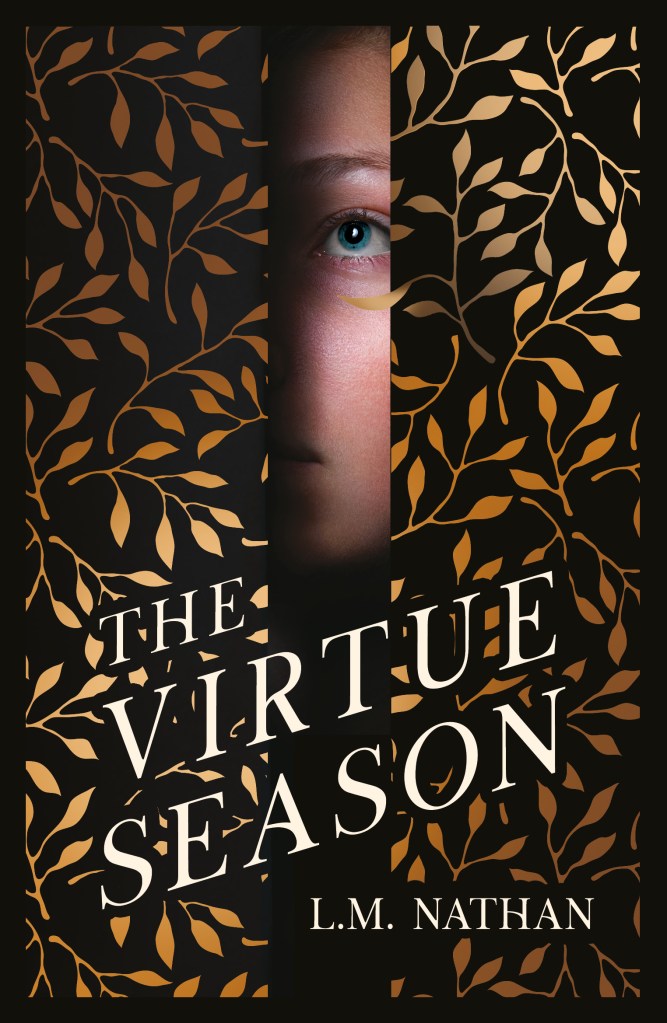

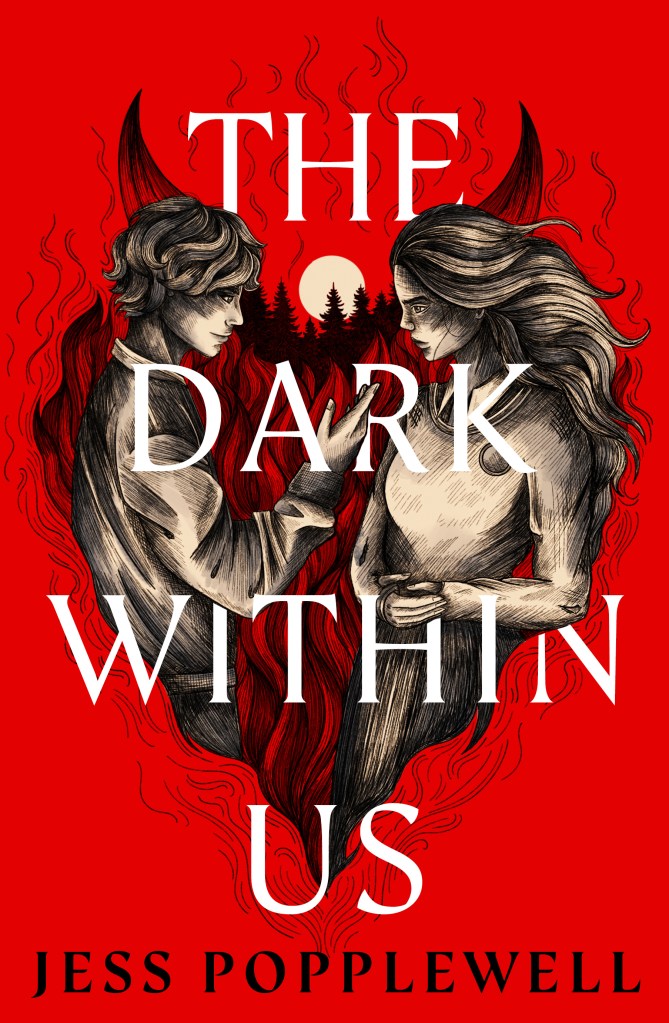

Jess Popplewell chatted to us about her writing journey and her new YA novel The Dark Within Us!

Could you introduce us to your novel, The Dark Within Us, and the inspiration behind it?

Of course! The Dark Within Us follows Jenny, a 16-year-old girl who is having a rough time. She’s fallen out with her mum and is therefore sleeping on her auntie’s sofa, which is clearly unsustainable. She’s fallen out with her best friend and been dumped by her first boyfriend – so when she meets a boy at a party who claims she doesn’t have a soul, this makes a weird sort of sense. Maybe if she can get her soul back, she can fix everything else as well. So, she decides to go with Luc – who it transpires, is a demon – into Hell in search of her soul. It’s inspired by a lot of things – not only did I leave home quite young, I also used to host for a youth homelessness charity so the idea of teenagers surviving via sofa-surfing is something I feel very strongly about. The book’s set sort of roughly in 2006, which is when I was a teenager, so I’ve also taken inspiration from TV, books and music of that era, most notably the TV show Skins.

The book features a modern version of hell, inspired by Dante’s Inferno. Can you tell us a bit more about how you created this setting, and more about where the idea came from?

Yes! When I was a teenager, I was a massive Goth and obsessed with religious and mythological perceptions of the afterlife. Some people get into horses and dolphins, I was slightly more morbid. I was always specifically interested in the way that rituals and beliefs around death evolve across cultures and over time – so I liked the idea of a modern teenager confronting centuries’ old beliefs and conceptions of the afterlife, especially ones like Inferno that have had such an influence on popular ideas of it even today (particularly in the West).

Despite the supernatural elements of the novel, Jenny feels very real as a character. She’s going through things that many young people today will be able to relate to. How did you go about creating her? And what do you hope readers can take away from this story?

That’s a lovely thing to say, thank you! I have been known to say that Jenny is a cooler version of me as a teenager, but that’s not the whole truth. She was conceived more as someone I might have been friends with – I imagined her with my group of friends, and her personality was influenced by that. Also, as I mentioned earlier, I have some experience of working with young people, and I genuinely think teenagers are the most interesting people on the planet, mostly because they’re doing a lot of work all the time in figuring out how to navigate the complicated stuff life chucks at us. I wanted to show that through how Jenny navigates… some seriously complicated stuff.

There are some other wonderful characters in this book. From the twins, Chloe-Lee and Joey, to the Ferrier and even Zillah! Did you have a favourite character to write?

In some ways no, because I do love all the characters in this book (well, maybe not Amber), but in terms of fun, probably Chloe-Lee and Joey. They’re such cryptic little weirdos, and cryptic little weirdos are almost always my favourite characters in any media. I’ve written so much backstory for them that had no place in the book, they still pop up in my head all the time.

Could you tell us a little about your journey to publication?

Sure, how long do we have? The very first iteration of this book came about when I was 16. Over the years, characters have come and gone, plotlines have shifted, the relationship between Jenny and Luc has been wildly different, but the things that have always been the same are that Jenny starts out homeless, she goes to Hell because of Luc, and it’s heavily influenced by Dante’s Inferno and mythological references. I’ve written other things as well, but when the 2022 Chicken House Prize came around I knew this was the story to submit. For one thing, they ask for a full manuscript and this one was somewhat finished. I was in Reykjavik with a friend when I discovered I’d won, and Icelandic people seem to love ice cream an appropriate amount so we went out after the phone call and I had a mint choc chip in celebration. I met my agent through the prize as well, since she was one of the judges, and the whole process was incredibly positive. I’m so grateful the judges got what I was trying to do.

What would be your top three tips to any aspiring writers out there?

One: find a way to make time, whatever that means for you. For a long time I was working multiple jobs, or studying and working at the same time, and that’s the main reason it took me so long to write the book, because I just didn’t have the headspace for writing unless I was forced to by doing a writing course or my Creative Writing MA. It’s easier now because I know I’ve done it once and can do it again, but when you’re at that early stage it’s important to think about what you can do to make it happen.

Two: at the same time, don’t make yourself ill with the pressure. If you have lots of other responsibilities (parents, I don’t know how you do it!!), writing is often the thing that goes on the backburner, and that’s OK. Don’t beat yourself up over it. Remember that daydreaming the next scene you want to write before you get chance to write it… counts as writing!

Three: to help with the above, explore different ways of writing. Personally I use the notes app on my phone to jot down random dialogue snippets or an especially productive daydream. I like it because I can email it all to myself in one go when I’m next at my PC. I’ve also played a bit with speech to text dictation – I’m not great at the punctuation yet but it’s a great way to get quite a lot of work done in a short space of time, even if it all needs editing later on. You can’t edit an empty page, so something is better than nothing!

You can’t edit an empty page, so something is better than nothing!

Are you able to tell us about anything else you’re working on, or that we can look forward to soon? Will there be any other stories set in this world?

I usually have 7 or 8 projects on the go at any given time – some of them are just for fun, like a 5-book series planned out in a cyberpunk dystopia (I call those projects my palate cleansers), but I’m also working on a couple of more serious projects. I do have ideas for more stories set in the world of The Dark Within Us; I’d love to write a follow up inspired by the themes in Purgatorio, but we’ll have to see if that pans out!

.

Jess Popplewell

Jess Popplewell is the author of The Dark Within Us, winner of the Times/Chicken House Chairman’s Prize 2022. She’s also a careers advisor in Higher Education, and has a series of free Careers Advice for Writers videos on TikTok (@jesspopps) and her website (jesspopplewell.com).

The Dark Within Us is published by Chicken House and out now.